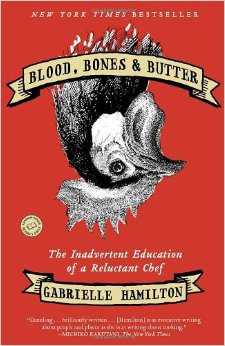

You can feel her amazement as her father roasts whole lambs on a spit and her awe at the dexterity with which the chef André Soltner pulls off a perfect omelet, using only a fork. She’s recounting actual rapture, not contriving its facsimile on cue. There are rhapsodic passages aplenty about eating and cooking, and while such reveries can easily seem forced or trite, hers ring sweetly true. Recalling her mother’s penchant for heavy eyeliner, she flashes back to “the smell of the sulfur every morning as she lit a match to warm the tip of her black wax pencil.” Hamilton invokes the “voluptuous blanket of summer night humidity,” captures the tantalizing promise of delicate ravioli by observing that “you could see the herbs and the ricotta through the dough, like a woman behind a shower curtain,” and compares breast feeding to being cannibalized, “not in huge monster-gore chunks, but like a legion of soft, benign caterpillars makes lace of a leaf.” It’s a story of hungers specific and vague, conquered and unappeasable, and what it lacks in urgency (and even, on occasion, forthrightness) it makes up for in the shimmer of Hamilton’s best writing. “Blood, Bones and Butter” traces nearly all of Hamilton’s life and career, from an unmoored childhood through her triumph at Prune, which didn’t end the search for a sense of place and peace that is the overarching theme of this autobiography, as of so many others. So the growing ranks of the restaurant-obsessed have been able to feast not only on her deviled eggs but also on her prose.Īfter much anticipation, the inevitable memoir has arrived. For many years now, she has popped up in prominent publications as the author of eloquent, spirited glimpses into the heart, mind and sweaty labor of a chef. But there’s another explanation: Hamilton can write. It owes something as well to her success as a woman in a field still dominated by men.

That’s principally because what she has championed at Prune - hearty comfort food prepared to a gourmet’s standards and served in a manner so unceremonious that the utensils don’t always match - foreshadowed some of the most prominent dining trends of the day. Just this one cramped, irresistible nook with its scuffed floors, nicked tables and servers in pink.Īnd yet Hamilton’s renown among, and even beyond, the food cognoscenti is huge. Prune has no annex or uptown sibling there is no Prune Dubai.

The restaurant she opened in downtown Manhattan in 1999, Prune, has barely enough room for the 30 diners it squeezes in at brunch, lunch and dinner, and despite the reliable presence of dozens of additional customers waiting on the sidewalk, she has either escaped or resisted the itch for expansion that so many of her contemporaries scratch and scratch. It’s hard to think of another American chef who has outdone Gabrielle Hamilton in converting the humblest of stages into the heftiest of reputations.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)